An Unprecedented Cross-Border Data Regulatory Regime: The Biden Administration Announces New Program to Shield Sensitive U.S. Data

The Biden Administration recently announced its plan to create a new regulatory regime governing the transfer of certain sensitive data from the United States. A new Executive Order (“E.O.”) issued on February 28, 2024, seeks to limit foreign adversaries’ ability to collect certain sensitive American data that can be exploited for malicious purposes. This regime is a dramatic policy shift for the United States, which has long opposed restrictions on cross-border transfers of personal information and has no comprehensive privacy law or regulations.

While in its infancy, the regulatory regime will be unprecedented and will impact any entity operating in the United States that collects or sells data within the program’s ambit—making currently routine business decisions and activities potentially unlawful. The Biden Administration is seeking comments and input from the public, which will help shape the contours of this new program. Potentially affected entities should not hesitate to comment.

I. Why This Is Significant

- The proposed regime does not just regulate the sale of sensitive data; it regulates who can have access to the data, including employees, vendors, investors, and senior personnel.

- Entities that collect information from U.S. persons will need to scrutinize where their data goes, how it gets there, who has access to it, and how it’s protected. These entities will need to revamp their compliance, diligence, know-your-customer, and know-your-vendor programs to meet these new requirements.

- The proposed regulations will impose new cybersecurity requirements on entities that engage in certain types of data transactions.

- Violations may depend on the citizenship and location of individuals who access sensitive data—facts potentially difficult to ascertain.

- The risk of enforcement is real. The program will be administered by the U.S. Department of Justice (“DOJ”), which will wield both civil and criminal penalties.

II. Overview of Proposed Regulatory Regime

The new E.O., which builds on previous executive orders,[1] establishes a regulatory program (hereafter, the “Bulk Sensitive Data Regulatory Program” or “Program”) to prevent transfers of sensitive data of U.S. persons and sensitive U.S. government data to foreign countries that are considered a national security threat. The United States will now join dozens of other jurisdictions, including the EU Member States and China, in limiting the cross-border transfer of certain types of information. The E.O. designated DOJ as the lead agency for developing, implementing, and enforcing the new regulatory regime. Contemporaneous with the E.O., DOJ promulgated an Advanced Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (“ANPRM”) providing more granular detail about the regime and how it will operate. The publication of the ANPRM begins a 45-day public comment period (ending April 19, 2024), which allows parties to submit comments that DOJ will consider before finalizing the rules.

The Bulk Sensitive Data Regulatory Program, which is established pursuant to the President’s authorities under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (“IEEPA”), is intended to prevent foreign adversaries from: (1) collecting and purchasing sensitive data of U.S. persons or sensitive U.S. government data through legal means; (2) collating, leveraging, and exploiting that information with artificial intelligence and data analytics; and (3) using that information to facilitate malicious purposes such as cyber operations, espionage, and transnational repression. The stated intent is not to regulate all cross-border data flows from the United States; rather, the Program is intended to block U.S. persons or entities from selling specific types and volumes of data to certain counterparties.

Generally, the Bulk Sensitive Data Regulatory Program will apply to the transfer of specific sensitive data to “covered persons” linked to six countries of concern. Transactions involving sensitive data of U.S. persons are to be regulated based on the volume of data, although for transactions involving sensitive U.S. government data, there is no volume requirement. The ANPRM proposes a two-tiered system regulating data transactions: (1) transactions that are prohibited, and (2) transactions that are restricted, which may proceed subject to certain security requirements that will be promulgated by the Department of Homeland Security’s Cybersecurity Infrastructure Agency (“CISA”). The E.O. and ANPRM repeatedly state that the Program will not cover the domestic transfer of these types of sensitive data.

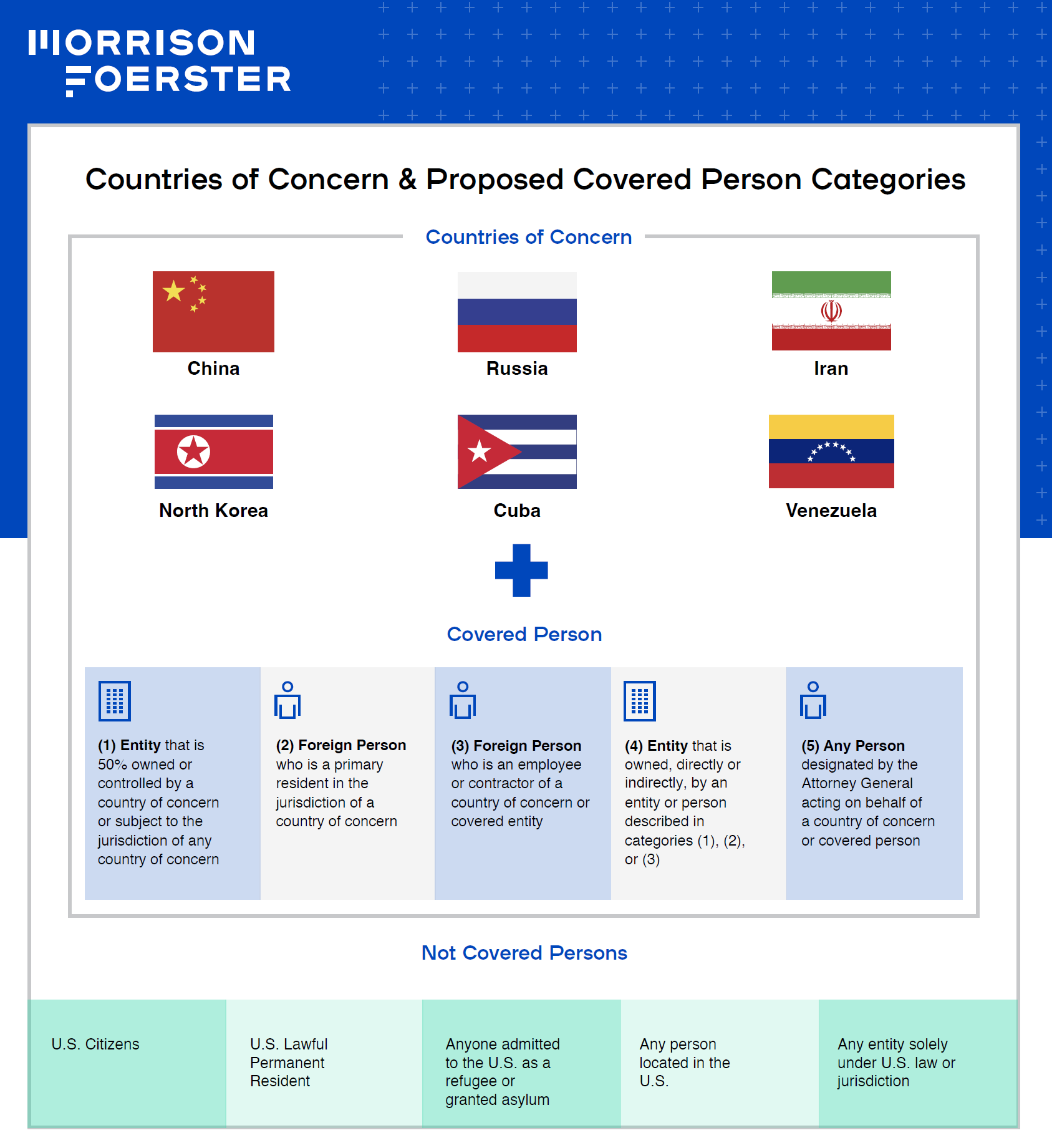

A. Countries of Concern and Covered Persons

The Bulk Sensitive Data Regulatory Program is intended to cover transactions with certain counterparties (covered persons) that are connected to six countries identified as “countries of concern” – China, Russia, Iran, North Korea, Venezuela, and Cuba.[2] As shown in the graphic below, the ANPRM lists five ways in which an entity or individual may be connected to a country of concern in order for the regulations to apply. The Program also allows the Attorney General to designate specific persons linked to or acting on behalf of these countries of concern. Such designated individuals would be on a public list.[3] Critically, and as discussed below, a person or entity need not be designated in order to be subject to the Program.

The ANPRM also makes clear that the Program would not apply to data transactions involving entities or persons that have connections to the United States. For example, citizens of countries of concern who reside in the United States or a non-listed country would not be considered a covered person unless they were individually designated by the Attorney General.

B. Data Categories

The Bulk Sensitive Data Regulatory Program would regulate two types of data.

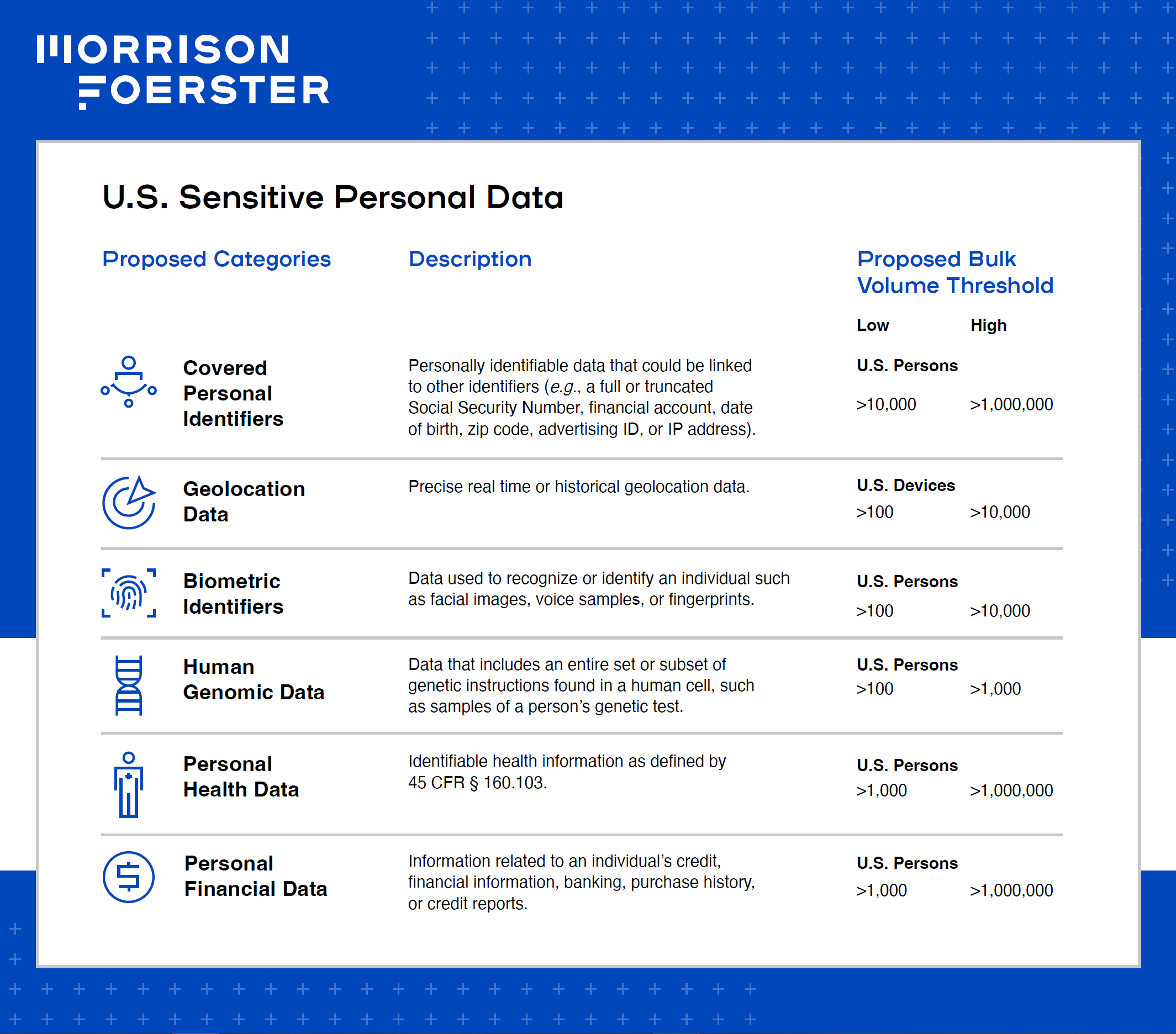

1. Sensitive Personal Data: The ANPRM defines six categories of sensitive personal data to be regulated: personal identifiers, geolocation data, biometric identifiers, human genomic data, personal health data, and personal financial data. A regulated transaction must be with a covered person, involve one or more of the six types of sensitive personal data, and exceed certain volume thresholds. These thresholds will be determined by a risk-based assessment that will account for the characteristics of each type of data. DOJ has proposed low and high thresholds for each category, as described below, and is seeking public comments on those proposed thresholds.

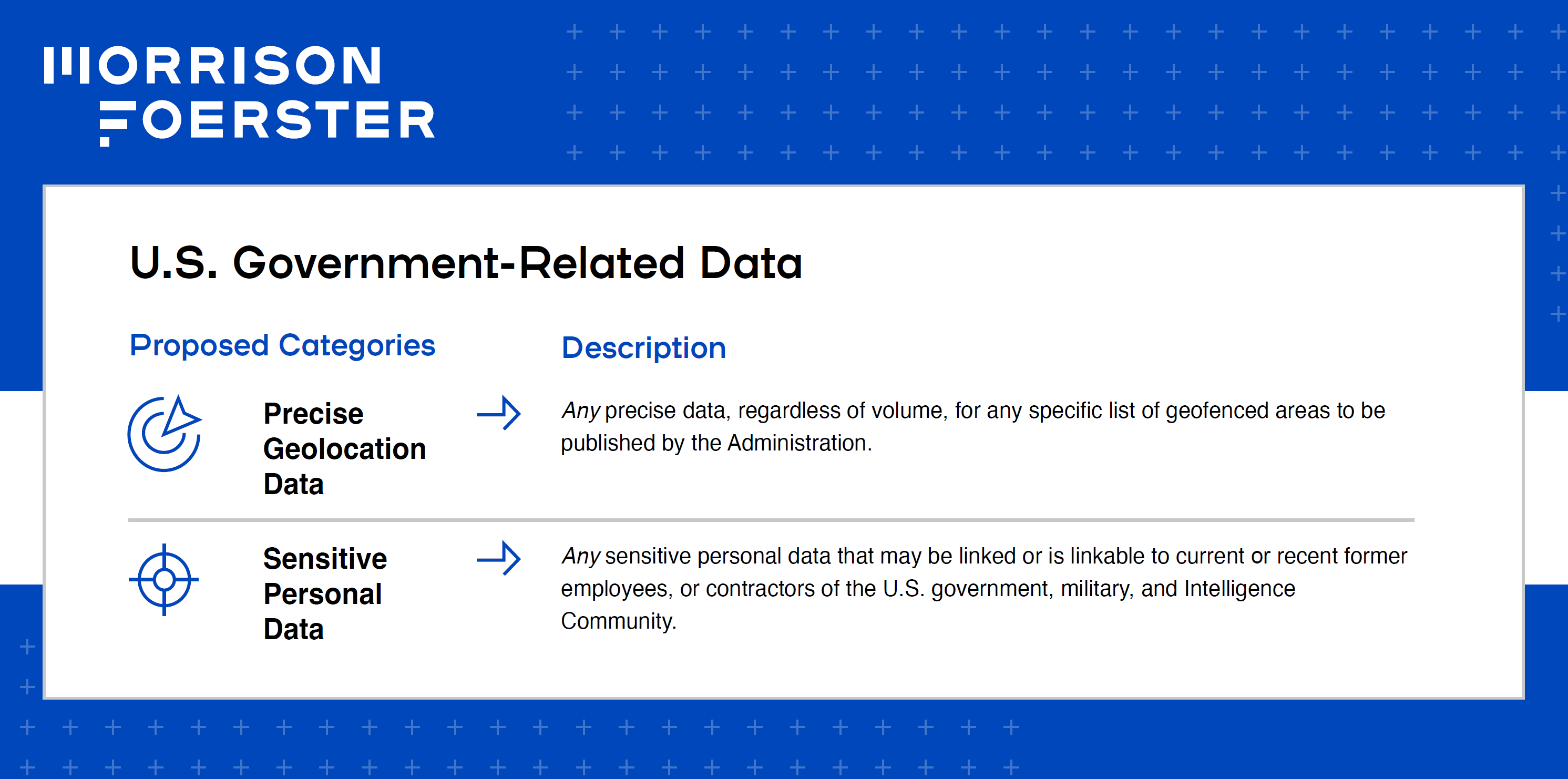

2. Government-Related Data: Transactions with covered persons involving government-related data, or data relating to government geolocations or attributable to government and employees and contractors, will be prohibited, regardless of volume.

C. Affected Transactions

The Program creates a two-tiered system for transactions covered by the regulations. Certain types of transactions are prohibited regardless of the type of data; other data transactions are merely restricted and could proceed if they meet the conditions and security requirements that will be promulgated by CISA.

1. Prohibited Data Transactions

- Data-Brokerage Transactions: As currently proposed, “data brokerage” is defined as the sale or transfer of data from any person to a recipient that did not collect or process the data directly from the individual to whom the data relates. For example, if a U.S. organization maintained bulk personal health data, and they license that data to a covered person, it would constitute a prohibited transaction.

- Genomic Data Transactions: Genomic data transactions involve the transfer of bulk human genomic data or biological specimens from which such data can be derived.

2. Restricted Data Transactions

- Vendor Agreements: Vendor agreements are defined as an agreement for goods or services, including cloud-computing services, in exchange for payment. For example, if a U.S. company collects bulk precise geolocation data from U.S. users on a mobile application (“app”) and enters into an agreement with a covered person to process and store the data, the U.S. company would be engaging in a restricted transaction.

- Employment Agreements: An employment agreement is any agreement or arrangement for employment (not independent contractors), including on a board of directors or committee. For example, an app provider that collects bulk sensitive personal information and intends to hire an executive who is a covered person and would have access to that data, could be engaging in a restricted transaction.

- Investment Agreements: Investment agreements are any agreement in which a person obtains direct or indirect ownership of a U.S. legal entity or real estate in the United States. DOJ provided an example of a restricted transaction: a foreign private-equity fund, located in a country of concern, agrees to provide capital for the construction of a data center for a U.S. company that stores sensitive data in exchange for acquiring a majority ownership stake in the data center.

The E.O. directs DOJ and CISA to establish the security requirements applicable to restricted transactions, which will be designed to mitigate the risk of access by countries of concern or covered persons. The ANPRM contemplates that a restricted transaction would be permissible if the U.S. entity:

- implements cybersecurity requirements;

- conducts compliance to ensure the data transaction is subject to data minimization and masking, uses privacy-preserving technologies (e.g., encryption), and implements systems to prevent unauthorized disclosure and logical and physical access controls; and

- satisfies compliance-related conditions (e.g., independent audits).

D. Exemptions

Several categories of transactions will be exempt from these regulations:

- Transactions ordinarily incident to and part of financial services, payment processing, and regulatory compliance. Examples include banking, capital-markets, or financial-insurance activities; the provision or processing of payments involving the transfer of personal financial data or covered personal identifiers for the purchase and sale of goods and services; and legal and regulatory compliance;

- Transactions ordinarily incident to and part of ancillary business operations (such as payroll or human resources) within multinational U.S. companies;

- Activities of the U.S. government and its contractors, employees, and grantees, such as federally funded health and research activities; and

- Transactions required or authorized by federal law or international agreements, such as the exchange of passenger-manifest information, Interpol requests, and public health surveillance.

The Program contemplates exempting types of investments by category that do not convey rights that pose an unacceptable national-security risk by giving countries of concern or covered persons access or influence to data within the ambit of the Program. For example, such exempted transactions could include publicly traded securities, investments in index funds or mutual funds, and investments made as a limited partner into a venture capital fund. These carve-outs are meant to ensure that cross-border commercial data flows are not impacted by the Program, in line with the Administration’s expressed goal of ensuring that the U.S. remains a global economic leader and protector of cross-border data flows.

E. Program Mechanics

The Program’s structure and definitions will be modeled on existing U.S. regulations based on IEEPA, such as those administered by the Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Asset Control and the Commerce Department’s Bureau of Industry and Security. Like those programs, the Bulk Sensitive Data Regulatory Program will establish processes for DOJ to issue general and specific licenses, so the Program will not operate on a transaction-by-transaction basis like the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States. To supplement general and specific licenses, DOJ will also issue advisory opinions in response to requests from entities, similar to DOJ’s Foreign Agent Registration Act and Foreign Corrupt Practices Act regulatory programs. These actions will give DOJ the flexibility to exempt, alter the conditions for, or allow wind-down periods for certain categories of otherwise-regulated transactions, and give parties an opportunity to apply for an exception to the rules.

Once the Program is implemented, individuals who fail to comply with its prohibitions or conditions could face civil or criminal penalties under IEEPA, similar to those under U.S. economic and trade sanctions programs.

III. Outlook

There are several major takeaways from this announcement.

- The Program does not just regulate the sale of sensitive data; it regulates who has access to the data. Although the Program is not intended to prevent all transactions with countries of concern that involve the data of U.S. persons, as drafted the Program still appears to cast a very wide net. Given the broad categories of data and transactions potentially covered, parties will need to understand (1) whether they handle the categories of sensitive data and (2) who has access to that to data, including members of the board of directors, investors, third-party vendors, and affiliates.

- Intra-company data flows and access will need to be scrutinized. As currently conceived, the Program could restrict or prohibit intra-entity data transfers (i.e., transfers between affiliates)—but only certain types. The ANPRM is considering exempting transactions to the extent that they are: (i) between a U.S. person and its subsidiary or affiliate located in (or otherwise subject to the ownership, direction, jurisdiction, or control of) a country of concern; and (ii) ordinarily incident to and part of ancillary business operations (e.g., sharing sensitive personal data for human-resources purposes, payroll transactions, etc.). This exemption will not apply to transactions that do not meet this criterion; for example, transactions involving the transfer of aggregated bulk personal financial data to a subsidiary that is a covered person. Companies with operations or affiliates in countries of concern will need to assess their operations and data access to determine if they are engaging in activities that may become unlawful.

- Citizenship and location of individuals who access data may be the basis for liability. Citizens of countries of concern who reside in the United States are not covered by the Program unless individually designated, and citizens of countries of concern located in third countries would not automatically be treated as covered persons either. But if a U.S. company hires an employee who is a covered person and that individual has access to restricted data, that could be considered a restricted transaction. The nuance to this framework is important; the ANPRM’s requirements do not flow from citizenship alone.

- The enforcement risk is real. Rather than setting up the program in Treasury or Commerce, the E.O. tasked DOJ with establishing a licensing process to authorize otherwise prohibited transactions and enforce violations. This indicates that the Administration expects DOJ to utilize its investigative tools and experience to identify and enforce violations. Ultimately, the U.S. government will now have a powerful new tool that can be adapted and expanded, via Executive Order or additional rulemaking.

- Compliance programs will need to be revamped—or overhauled. Current export compliance, sanctions, and data privacy compliance programs are unlikely to deal with the new framework. Organizations will need to examine: (1) the types of information they collect; (2) the entities or individuals to which they sell or with whom they share that information; and (3) the entities or individuals involved in data collection and processing. Entities should ensure compliance programs are updated accordingly.

Perhaps the main takeaway is that now is the time to share concerns with the Administration. The E.O. and ANPRM are only the first steps in this process. The subsequent comment period provides an opportunity for interested parties to submit feedback and shape the contours of the Program before it becomes operational. The ANPRM includes over 100 specific questions on some of the most difficult scoping and definitional questions and will be followed by draft regulations at a later stage of the process. Public comments for the ANPRM are due by April 19, 2024.

[1] See Executive Order 13873, Securing the Information and Communications Technology and Services Supply Chain (May 15, 2019); Executive Order 14034, Protecting Americans’ Sensitive Data from Foreign Adversaries (June 9, 2021).

[2] These are the same six countries that are covered by the Department of Commerce’s information and communications technology and services regulations.

[3] This public list would be similar to the U.S. Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control’s Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons list.